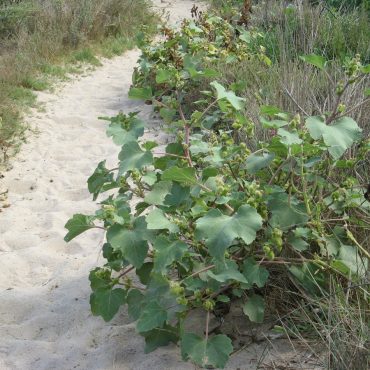

Cocklebur is an upright annual herb that may reach six feet tall. It is extremely variable in specific characteristics. There is usually one stem from a tap root. The central stem often produces ascending lateral branches that decrease in length toward the top. Stems are light green, with short, reddish streaks.

A basal rosette is absent. Cauline leaves are green and broadly ovate, up to seven inches (18 cm) long, with brownish petioles about as long as the leaf. Leaf margins are often shallowly and irregularly toothed and may be palmately lobed (somewhat like a maple leaf). Leaves and stems are made rough to touch by short, upward pointing hairs.

The individual flowers (or florets) are highly modified and don’t look like flowers in the usual sense. Individual florets are either male or female and are clustered on separate flower heads that occur in branched terminal clusters and in shorter axillary clusters. Male flower heads are found on the upper or outer portion of a cluster. The tiny male florets occur on a hemispherical receptacle. Male florets lack a pappus and have a tiny, symmetrical corolla. Each has five stamens; their filaments are united into a column around a sterile pistil. The anthers unfurl outward, looking initially like tiny yellow egg whisks. A female flower head consists of only two florets which lack pappus, petals or stamens and are enclosed by the egg-shaped receptacle. The receptacle is covered with overlapping leaf-like phyllaries, some of which are “hooked” outward at the tip. At the outer end of the green flower head are two larger projections, the “beak”, each of which is paired with a smaller tooth; between each beak and tooth, a forked style extrudes through a tiny pore. These are the only visible parts of the female florets. Cocklebur blooms July – October.1

The bur is a dry, hard ellipsoid or ovoid structure, roughly an inch (2.5 – 3.0 cm) in length. The bur encloses two fruits, each with one elongate seed; the seed of one fruit is somewhat larger than the other. The spines that cover the bur are derived from the leaf-like phyllaries that have grown and hardened into the hooks that make the cocklebur so aggressive.