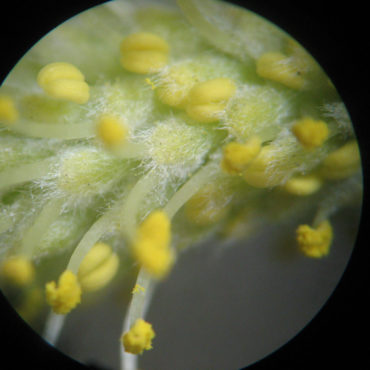

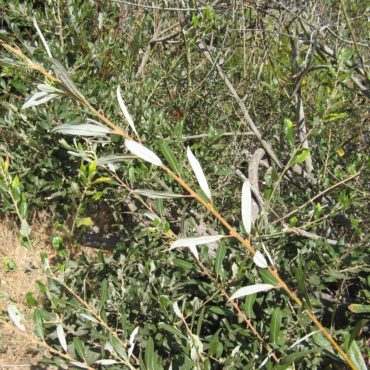

Compared with the tall, stately cottonwoods, sycamores and willows that reign over most of San Elijo’s wetlands, sandbar willows (Salix exigua) are dwarfs, easily overlooked, even with their silvery foliage. However, they often play a key role in the first chapter of a wetland. They are pioneer species, the first trees to inhabit a marsh or shore after a significant disturbance. They arrive as tiny airborne seeds and reproduce vegetatively, quickly forming dense patches of small willows that stabilize the terrain, and provide shade, protection and food for the initial animal inhabitants. Both the pioneering seeds and subsequent vegetation are intolerant of shade and are ultimately overgrown as other species become established.

Many of the sandbar willows in the Reserve were planted in the late 1990’s, following the physical removal of an invasion of giant reed (Arundo donax). These willows have done their job and are slowly giving way more permanent plants.