Description

2,4,26,59

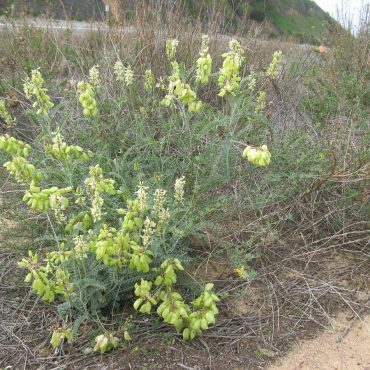

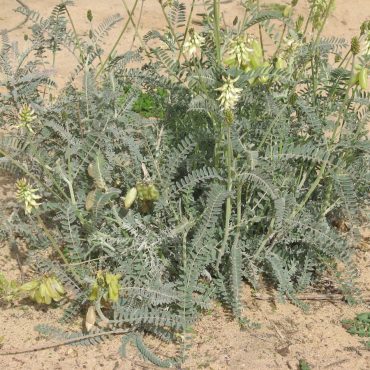

Ocean locoweed is a perennial herb that often dies back to the taproot in the summer. The plant is usually less than 32 inches (80 cm) high, and is composed of several upright to ascending branching stems covered with soft green foliage. Stems and foliage are made more or less silvery by a dense coating of short, white hairs. Parts of the plant may be lightly tinged with red.

The leaves are generally less than 10 inches (24 cm) long, pinnately compound with many sub-opposite leaflets. (As many as 48 have been reported.4)There are two small, triangular stipules at the base of each leaf. Leaflets are narrow to broadly ovate to obovate, sometimes notched at the end. Larger leaves are less than one inch long, decreasing in size toward the leaf tip.

The flowers of ocean locoweed are densely whirled on terminal spikes. The calyx is a five-pointed tube. The flower has the bilateral shape of a typical pea flower. It is crescent-shaped, arching down and out, about 1/2 inch (1.3 cm) long and greenish-white to cream in color. The petals are sometimes described with pinkish veins, but this is not evident in our plants. The upper petal is large and flares upward forming the “banner”. Two side petals (“wings”) are directed forward, enclosing the remaining two petals which are fused lengthwise into a “keel”. In turn, the keel encloses the male and female reproductive structures. There are ten stamens; one is free, and the filaments of nine are united into a ribbon and free only at the top; there is a single pistil. The stamens remain after the petals have dropped. Flowers begin blooming when the winter rains begin and continue through the spring usually January through June.1

The fruit is a one-chambered, inflated bladder-like pod, beaked at the outer end. Loose clusters of fruit droop from the flower stalk. Developing fruit are bright green, aging to kraft-paper brown. Up to 30 seeds are attached along the upper suture and, when dry, the fruit splits open along the lower suture.